How would a referendum on separation work?

Those who've been reading Cascadia Journal know that I support discussions about independence for Oregon and Washington as an escape plan from the US descent into fascism. Is this the best solution? I don't know. Would it be easy? Certainly not.

But with each passing day, some sort of autonomy for Cascadia seems like a more rational choice as democracy crumbles in the US and as the Trump administration bullies and arrests its political opponents, shuts down dissent, ignores court orders, engages in a mass deportation campaign conducted by masked thugs, slashes funds to states that oppose his rule – the list goes on and on.

To learn more about how Cascadia might achieve independence, I recently spoke with Hugh Spitzer, a retired law professor at the University of Washington who's an expert on constitutional law, wrote a definitive book on the Washington State Constitution and is also an authority on secession movements. His 1982 master's thesis, Secession from the United States of America: A Legal Analysis, looks at the history of secession in the United States and explores what pathways (if any) exist for states to leave the union.

"I tried to imagine, from a purely legal standpoint," Spitzer said in our interview, "whether it would be possible to structure a secession of some states from the United States under either American constitutional law, or under international law."

And though he found there is a constitutional process that would allow states to peacefully leave the union, Spitzer says the hurdles are immense. He notes, "that would require the approval of Congress. So you would have to consider whether that was politically feasible or not. I'm not sure it's very easy in the current situation, or 40 years ago when I wrote my thesis."

In his thesis, Spitzer notes that after the conclusion of the US Civil War, the 1869 US Supreme Court ruling Texas v. White attempted to retroactively declare the secession of southern states in the Confederacy illegal. Spitzer, in his thesis, observed that while such a declaration was reasonable after a grueling war, more recent changes in international law and notions of national sovereignty have made those arguments less relevant. He believes under certain conditions, secession would be legal.

Regarding international law, Spitzer notes that in the early to mid-20th century, when colonies held by European powers were declaring independence, international law moved to recognize concepts such as self-determination, and the rights of oppressed ethnic regions of certain nations to assert their independence. The international community shifted to supporting decolonization, and the independence movements in Asia and Africa were clearly part of this – even if nations treated them as internal domestic matters.

In his thesis, Spitzer says there could be a "non-legal" approach to separation in the US, in which a revolution (peaceful or otherwise) within a state or territory simply refuses the authority of the United States. To gain international recognition, such a movement would have to prove a certain people were seriously oppressed under the existing government (say, if Puerto Rico were suddenly denied all rights of US citizenship). But he's skeptical that a movement on the US west coast, for instance, could currently make that argument.

"In international law, secessions are viewed as being lawful where you have a highly oppressed ethnic group or religious group that wants to secede because of the oppression and violations of human rights," Spitzer said. He notes that the Quebec separatist movement from Canada had been making this argument for decades, but he remains skeptical that it's a strong one.

Spitzer did find in his thesis that the US constitution has three mechanisms that would allow for a separation by "mutual consent," or what's also known as "devolution," a peaceful, orderly process of a region leaving another nation.

First, and probably most effective would be by amending the constitution to remove the various states that want to leave. This, however, is also the most difficult pathway since constitutional amendments require approval by 3/4 of all state legislatures.

Second, Spitzer wrote that a treaty or an executive agreement, either of which could be negotiated and signed by the executive branch, could presumably be made with a new nation – say, Cascadia. Most treaties require the consent of the Senate, however, making this option politically difficult. Further, there might be opposition in Congress and federal courts if arrangements weren't made to guarantee that those in the affected territories be allowed retain their US citizenship if they choose to.

A third, and most likely path, Spitzer contends, is also through congressional approval (though again, Spitzer notes that in the current political climate it seems unlikely Congress would agree to this). In his thesis, Spitzer observed that an 1842 treaty approved by Congress, and agreed to by legislatures in Maine and Massachusetts, transferred about 12,000 square miles of border lands in the two states to Great Britain (which ruled Canada at the time).

A later court ruling affirmed the legality of this shifting of lands from several states to another country ("why not a new country?" Spitzer mused in his thesis) as long as the states involved and the federal government agree.

Spitzer then lays out steps in which a state might legally leave the union.

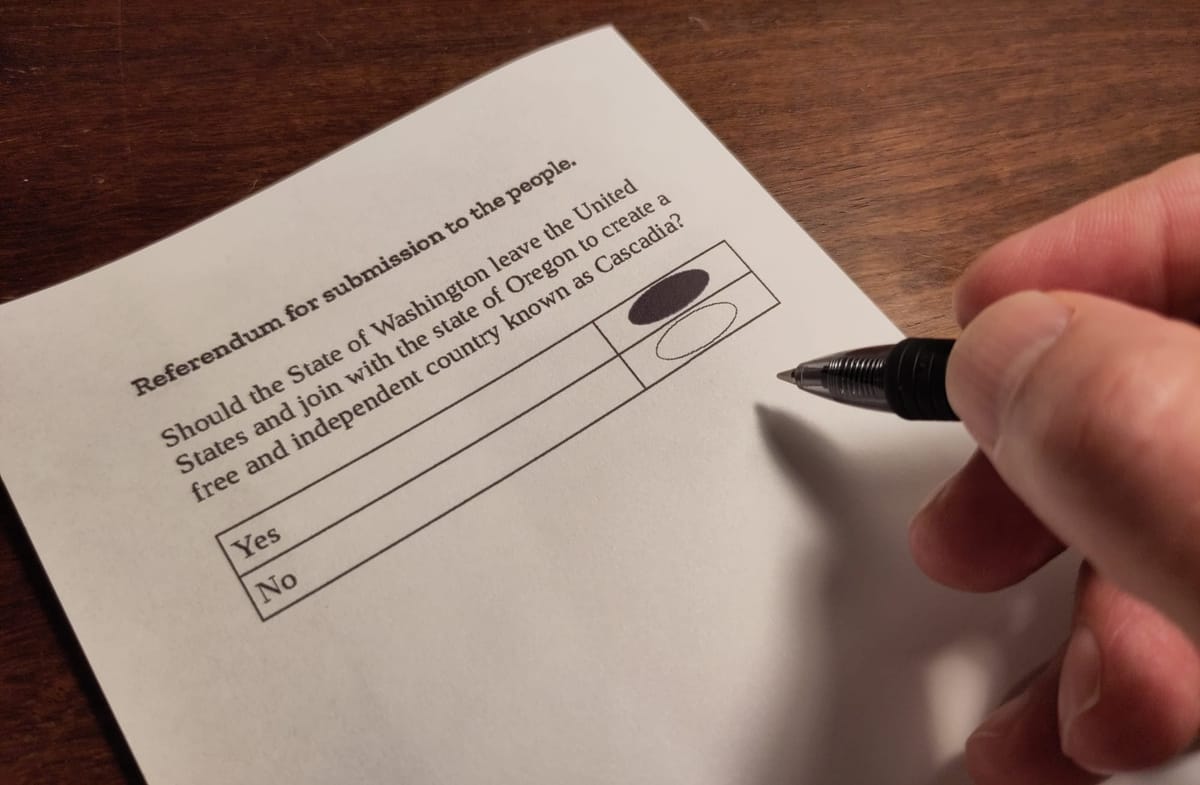

- Holding a "plebiscite" in a state on the question of separation (i.e. a statewide ballot referendum).

- Passage and signing of federal legislation specifying a timetable and process for separation. This would cover establishment of a national government capable of international recognition, options for citizenship, transfers of property, status of government jobs, pensions, debt allocation, and issues associated with defense and military installations.

- Signing of agreements between the US president and representatives of the new nation regarding international relations, trade, diplomatic offices, etc.

- The new nation would then apply for recognition with the United Nations.

Spitzer told me that while there is a legal pathway, he believes it's very unlikely in the current moment that all parties would willingly agree. In addition, a state referendum on independence (which, Spitzer notes, is absolutely legal under Washington and Oregon law) would need strong support in order make such a course of action politically viable.

"I'm not a political scientist, but my gut feeling is that you certainly need more than two thirds, and maybe you need north of 80 percent" to validate a call for independence, he says.

Have there been peaceful separation movements in the past that could be a model for Washington and Oregon leaving the union? Yes, Spitzer says. He points to the separation of Norway and Sweden in 1905. Norwegians held a referendum, and after it passed, worked to fire the Swedish king, choose their own king, and then establish itself as a fully independent nation. Like US states, Norway already had a strong, functioning domestic government, but had granted Sweden the right to run the nation's military and represent it diplomatically in most international affairs. The separation went peacefully, even though a few people in Sweden had called for military resistance.

There are other examples – most notably, the independence of the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia from the Soviet Union during the "singing revolution" that occurred between 1987 and 1991. The separation occurred non-violently, though it should be noted the Soviet Union's constitution actually allowed republics to leave the union at their discretion.

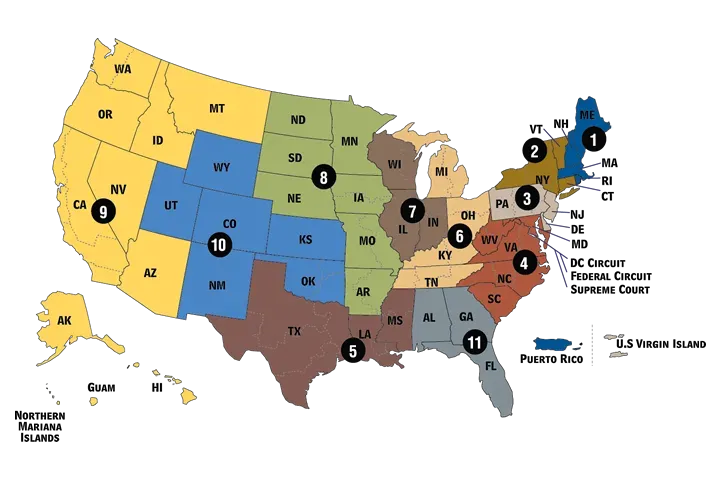

Spitzer says he's skeptical that outright secession for states such as Washington, Oregon, or California would be a politically viable way to solve growing problem of populous states increasingly losing the ability to influence policy. He notes this imbalance occurs mostly because of the oversized power of the Senate.

Spitzer has proposed an intriguing solution to this problem: states agreeing to combine into "mega-states" so that the current 50 would be reduced to the original number of 13 that existed when the constitution was first written.

He says states could agree to do this through congressional action and that this wouldn't require a constitutional amendment. Perhaps one mega-state would include Washington, Oregon, and California, though Spitzer admits he hasn't sorted all the details of his plan. "They could do a better job, just like the provinces in Canada, which are much stronger than the states in the US."

Regardless, it's clear each path toward independence or consolidation for states faces daunting hurdles. But considering the dire situation the Trump administration has created for US democracy, I'd insist they're ideas worth investigating.

--Andrew Engelson