What places are part of Cascadia?

One of the most common questions I'm asked when talking about Cascadia independence is: what exactly is included in Cascadia?

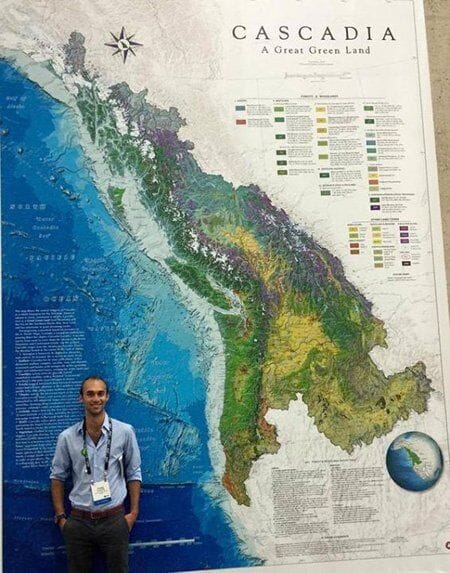

I find there are two answers to that question. The first involves what we mean when we're talking about the Cascadia bioregion. This vast, interconnected web of ecosystems extends from the glacial fjords of southeast Alaska to Cape Mendocino in far northern California. It extends east into the watersheds of Columbia, Snake, and Fraser Rivers and generally encompasses the native range of Douglas-fir trees (hence the emblem on the Cascadia flag).

The Cascadia bioregion includes all of Washington, much of Oregon, most of Idaho, some areas of western Montana, and even the Yellowstone region of Wyoming. It includes all of western British Columbia and most of the central province as well. To the north it encompasses southeast Alaska, and stretches south to include the northernmost section of California.

According to Cascadia Department of Bioregion, if the Cascadia bioregion were an independent nation it would be the 20th largest country in the world, with a surface area of 534,572 square miles, or 1,384,588 square kilometers.

The more complicated question is political. When we talk about an autonomous or independent Cascadia, what current states or provinces are part of that movement?

In this newsletter, and in my work for the grassroots organization Cascadia Democratic Action, I'm fostering discussion about political independence for only Oregon and Washington. (At Cascadia Journal, I also cover news from British Columbia, Idaho, and occasionally, Alaska.)

So why leave out the rest of the bioregion in the movement for separation?

The obvious answer for Idaho and Montana is that the majority of residents in those states are quite fine with Trump's fascist MAGA project and any talk of joining a more progressive, independent nation would be met with strong opposition.

As for California, I'm all for the state's northern counties joining our efforts, but generally most talk of California separation has been about one unified state. And I'm not a fan of the idea of a larger, unified western states secession movement. I believe the Pacific Northwest's interests would likely be overshadowed if we were to join in union with our 39 million neighbors to the south of us.

Plus, Gavin Newsom is a douchebag. But, I digress.

We would very much welcome the province of British Columbia eventually joining us in a fully united Cascadia. Of course this would require some shifting and conjoining of different governmental structures, but I don't think the process would be insurmountable.

However, the primary issue with British Columbia joining Cascadia is that pro-Canada patriotism is surging at an all time high in the province. That's thanks to our common foe: Donald Trump. Though BC certainly has its issues with Ottawa and there are plenty of Cascadia supporters all over western Canada, the fact remains that enthusiasm for separation in BC is low at the moment.

The wild card in this situation is the Alberta separatist movement, which is extremely conservative, pro-MAGA, and has had direct conversations with Trump officials. If the "Texas of Canada" were ever to break away and even seek admission the US, British Columbia might have more incentive to break off and join Cascadia if they become physically separated from the rest of Canada.

There are plenty of other complicating political factors in the Cascadia separation movement, not least of which is that areas east of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington are generally more conservative and supportive of Trump. But there are cracks emerging – including farmers and orchardists hurt by tariffs and mass deportations diminishing their workforce. Spokane is quickly becoming more progressive. And if eastern Oregon wants to follow through on the right-wing Greater Idaho movement, well... godspeed.

For now, we're focusing discussions about autonomy on Oregon and Washington. That's as good a place to start as any.

--Andrew