Imagining Cascadia as a postnational nation

The idea of Cascadia has always been a bioregional concept rather than a nationalist project.

But the current authoritarian and constitutional crisis is the United States has forced those of us who live in US states within the Cascadia bioregion to consider alternatives to remaining within the US framework.

I believe we must work toward increased autonomy for Oregon and Washington – whatever that may look like – and I also believe Cascadia could serve as the first truly postnational nation. As we non-violently resist and move toward independence, Cascadia should question and seek to reform institutions that the global system of nation-states relies upon.

Those systems we should question include strict limits on who is considered a participating citizen of a nation, controls on migration and movement across borders, the failure to tax wealth on a global scale, denial of universal human rights to certain residents, and a failure to recognize and empower Indigenous people.

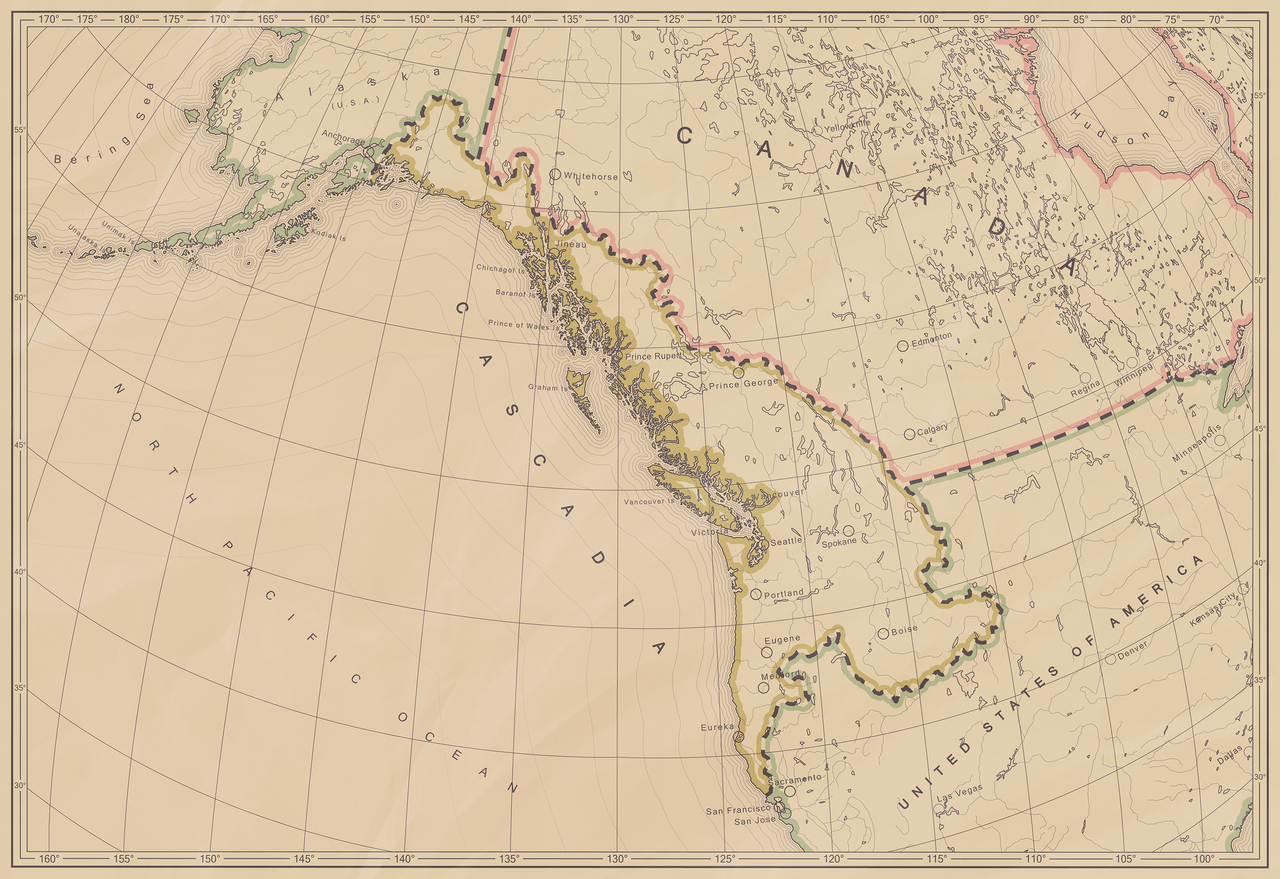

Bioregionalism is a philosophy that believes human and ecological systems will function better if organized around naturally-defined bioregions. These large regions are defined by interconnected watersheds, ecosystems, and human populations. As I've written previously, the Cascadia bioregion extends from southeast Alaska to northern California and east into the watersheds of various rivers in the Pacific Northwest, including the Fraser, Columbia, and Snake Rivers.

While many bioregional activists would argue that thinking about Cascadia as a nation-state is counter to the spirit of the movement, I would argue that two major crises have forced us to rethink that opposition. The first is the descent of the United States into fascism, and the ruling regime's dedicated opposition to the health and safety of Cascadia's people and ecosystems. The second is anthropogenic climate change, which the current global system of nation-states is failing to address and could prove disastrous if we fail to act.

As the US abrogates the constitutional framework that serves as a contract between the states and the federal government, as well as actively working to stifle solutions to the climate crisis (trying to force a coal-fired power plant to remain open to cite just one example), the people of our region have a right – and indeed an obligation – to move toward autonomy.

As our region moves toward independence, this could mean beginning to push against the federal the system of taxation and government allocation of funds, which is increasingly stacked against Cascadia. It could mean soft secession tactics like joining the Western State Health Alliance to protect our residents' health. It may look like pooling resources to build a regional high-speed rail system.

It will also require resiliency at the local level: building mutual aid networks to support immigrant neighbors hiding in fear; helping out those who can't afford food or basic needs as inequality increases; supporting local businesses, co-ops, and arts organizations that serve the communities we live in.

But on a larger scale, what would a post-national nation look like?

In her 1995 academic work Limits of Citizenship, Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal argues that an increasingly global and interconnected economy is creating unique, post-national communities. Migrants and guest workers in northern, wealthy nations are challenging accepted notions of what a citizen of a nation can or should be. In addition, global multinational corporations now transcend national borders and agreements like the EU and NAFTA allow wealth to cross borders and evade national tax systems.

Soysal imagines the need for universal citizenship – based on a recognition of universal human rights – as an alternative to nation-based citizenship. And while the current political climate is unfriendly to this idea, I think it's one that Cascadia should give a voice to while it also asserts its determination to become an autonomous nation-state.

The fierce right-wing, nationalist political backlash against these postnational immigrant communities (whether "legal" or "undocumented") is driving authoritarian governments to take hold in Europe and North America. Part of the ferocity of this movement is a realization that old nationalist conceptions, often rooted in racism or ideas of cultural superiority, are at risk of losing their privileged status. The MAGA movement began as a reaction to the election of a Black president. And Trump insisted on building a physical wall on the US-Mexican border because he realized that nations are fictions. The theorist of nationalism, Benedict Anderson, correctly called nations "imagined communities."

A post-national nation could begin to question that imaginary system. It's a system that allows a person from Texas to work in Seattle, but prevents a person from Guatemala from working in Seattle. A postnational nation could demand a binding global agreement with enforceable limits on greenhouse gas emissions. Cascadia could argue that when billionaires are allowed take their wealth to tax havens in Bermuda, the global economy becomes plagued by inequality. We could argue that funding global health initiatives like the eviscerated USAID are essential to the well-being of us all.

Economist Thomas Piketty is perhaps the most prominent voice for a postnational society, insisting that the only way to effectively deal with global inequality is an international tax on wealth. In his book Capital and Ideology, Piketty makes it clear that our current system of global hyper-capitalism is choice – and a choice that we can chose to reject.

I believe that those of us who think of ourselves as Cascadian don't need to choose between bioregionalism and nationalism – that we can work toward both visions. But we must also acknowledge that the current system of nation-states is extremely flawed and needs to be reformed. Or perhaps replaced with something new and better-suited to protecting universal human rights, addressing inequality, and creating more sustainable global and local economies.

It's important to remember that all of us who live in the Pacific Northwest are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants – though the Indigenous people who have been here since time immemorial should be accredited a special status.

I firmly believe that anyone who resides within the Cascadia bioregion can call themselves Cascadian. And that, regardless of nationality or immigration status, each of us has a right to housing, education, health care, human rights, and a say in how human society in Cascadia functions.

That may be a radical idea, but it's one our bioregion needs to debate and consider as we push back against the virus of fascism and create an alternative here in our corner of the continent. --Andrew

Do you appreciate Cascadia Journal's exclusive reporting on the ways the Pacific Northwest is pushing back against US fascism? If you have the means, please consider a paid subscription of just $5 per month. Each subscription helps me produce original reporting and opinionated notes on Cascadia's fight to build a more resilient and autonomous bioregion. And to those who already subscribe, thank you! --Andrew